A letter to my church family about the history of anti-Asian racism in America

Dear Forefront Family,

I’m writing this to you all because many have been asking what they can do about anti-Asian racism, especially in light of the recent violent attacks on Asian Americans, a community that is a valued part of our church.

It’s unclear if all the attacks were racially motivated, but the attacks have to be situated in a climate that is marked by a 150% increase in hate crimes against Asian Americans in cities last year, with the biggest increase in New York City, thanks no doubt to the former administration’s framing of COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus.” Several of my Asian American friends, including Forefront congregants, have told me stories of being verbally harassed on the streets or in hospitals for COVID-19. But this violence is by no means new, which I will explain more below.

I must say that I felt reluctant at first to publicly discuss the topic of anti-Asian racism for a few reasons, but I was inspired by our congregant, Judy Huang, who lives in California with her wife, Melissa, and who wrote this:

The recent hate crimes against the Asian community have brought up a lot of sadness in me. I am sad that I feel invisible. I am sad that I am forever seen as other. I am sad that evil seems to triumph. I am sad that I cannot be angry, as if the struggles of my community are dismissed because of the model minority myth perpetuated by white supremacy.

Often, I find that in conversations about race, Asians are made to feel that their experience is less relevant because of the stereotypes held about Asians. The feelings of never belonging, the feelings of otherness, the feelings of invisibility – these are not “bad” enough.

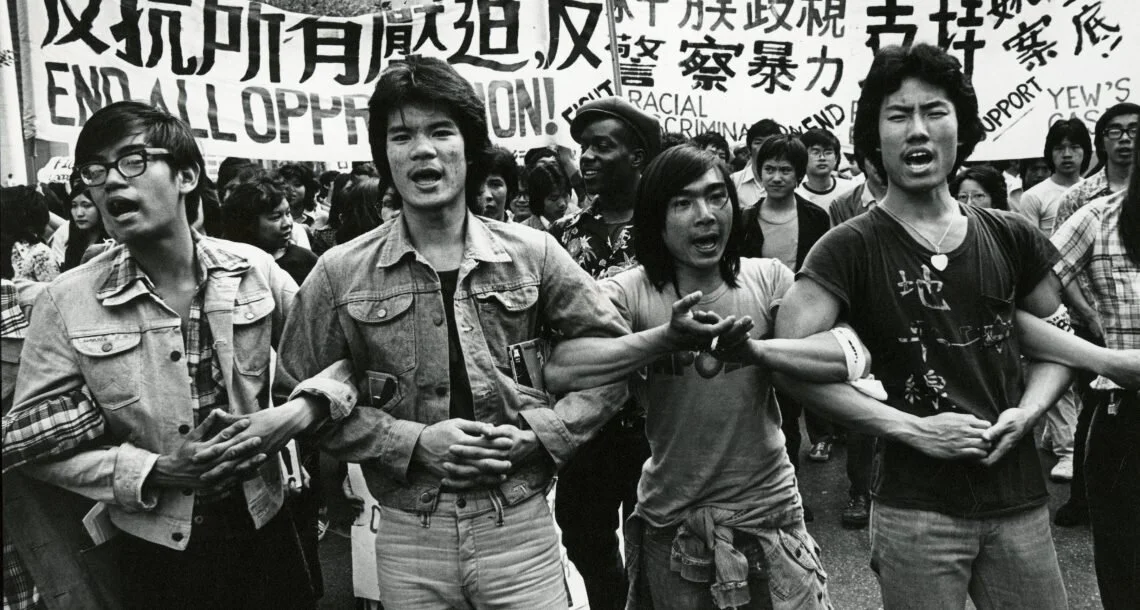

The photo is taken on May, 13 1975 by Corky Lee, a famous Chinatown photographer who recently passed. That day 3,000 people, mostly Chinese, took the streets for the first time to protest the NYPD’s beating and strip search of Peter Yew. Yew was a Chinese-American living in New York City's Chinatown when he witnessed police brutally beating a 15 year old for a traffic violation. He grew concerned and intervened, which led to his treatment. The New York Times reports that “demonstration that had young students protesting side‐by‐side with their parents and grandparents, chanting together in Chinese.”

The feeling that Asians are “other,” “foreign” or “invisible” dates back centuries. Since many do not know the long history of anti-Asian racism in America, I’m providing a very brief and incomplete primer to show that the current racism is, in fact, not senseless, but in keeping with the logic of exclusion and anti-Blackness in this country. We always like to say “you have to look at the context” in our Forefront sermons, so here is some context.

1790: Naturalization Act: Only free white persons can naturalize into citizenship

1854: People v. George Hall rules that Chinese testimony against white people is inadmissible and that Chinese and Indians should be grouped with Blacks as “nonwhites.”

1870: Congress extends right to citizenship to persons of African descent but excludes other non-white people, including Asians.

1875: Congress passes the Page Act of 1875, the first federal law restricting immigration, to “end the threat of cheap Chinese labor and immoral Chinese women.” This fear of Asian women as sex workers and demonization of them effectively banned all East Asian women from legally immigrating.

1882: The US passes the Chinese Exclusion Act, which bars all migration from China except for merchants, diplomats, and students

1910: Western states pass Alien Land laws which prevent “aliens eligible for citizenship” — Chinese and Japanese immigrants—from legally owning or leasing land

1924: The US passes the Johnson-Reed Act, completely prohibiting immigration from Asia, including Japan.

1942: The US rounds up 120,000 Japanese Americans, most of them born here, and places them in internment camps in reaction to Pearl Harbor.

1982: Vincent Chin, a Chinese man, is beaten to death by two white auto-workers who mistake him as Japanese in a climate of anti-Japanese sentiment and “Buy American” campaigns.

2001: The 9/11 attacks leads to hyper-surveillance and policing of Muslim Americans, many of whom are South Asian.

And countless more incidents...

The domestic suspicion of Asians as “inferior, foreign threats” works in tandem with imperialist wars against Asian countries deemed as “foreign [Communist] threats” or populated by “inferior, uncivilized” peoples who can’t govern themselves (but who have plenty of natural resources to take advantage of): The colonization of the Philippines from 1898 to 1946; the American overthrow of Hawaiian monarchy in 1893; the five million killed in the invasion and division of Korea from 1950 onwards; and the four million slain in the invasion of Vietnam from 1965 to 1970’s.

The logic that runs through everything is the belief that Asians are perpetually inferior foreigners. A good example is this “Yellow Peril” illustration of a Chinese devilish man stepping over a white woman, representing the West, in 1899.

More broadly, the fear of the foreigner includes more than Asians and applies to most immigrants. Andrea Smith names this fear as the third logic of white supremacy: (1) slaveability/anti-black racism, which anchors capitalism; (2) genocide, which anchors colonialism; and (3) orientalism, which anchors war.

These logics serve, among other things, to divide us. So when we as Asian Americans hesitate to talk about our pain because we don’t have it “as bad” means we are engaging in a comparative exercise (“Oppression Olympics”) that only benefits white supremacy. It’s far more productive to say that we can’t ever compare or claim to understand another group’s pain, but we must fight the fundamental force at work behind all three logics.

Moreover, many of these logics are interrelated, as Claire Jean Kim shows. After the civil war, white bosses imported Chinese workers partly as competition against freed Black workers. Chinese workers were seen as “more intelligent” than Black workers, but also as more “foreign” and thus more “docile.” A San Francisco newspaper in 1869 describes Chinese workers: “[he] knows and cares nothing more of the laws and language of the people among whom he lives will suffice to keep him out of trouble.” It’s in this way and many others that Kim argues Asian Americans are “triangulated” between whites and Blacks.

Today, the myth of the “model minority,” a term coined in a 1966 New York Times article by sociologist William Petersen, holds that Asian Americans succeed because they have strong “family values” and focus on economic progress, not political progress. That myth assumes Asian Americans “keep together” and stay out of politics and trouble. The myth hides the vast inequality within Asian Americans (i.e. 1 in 4 Asian Americans live below the poverty line in NYC) and serves as a useful weapon against those, especially Blacks, who demand political progress. In short, the myth does not serve anyone, only white supremacy (which is, I must add, different from “white people”).

As Judy wrote, “The most destructive lie that white supremacy has instilled in us is divisiveness. It is part of the playbook to increase tensions within marginalized groups, whether it be racial or socio-economic. When this happens, it divides the marginalized communities from within and fragments our ability to stand together.”

Let us stand together as one body in Christ, recognizing how we have been torn and set against each other through different logics so that we may become whole.

Who is alien? Who “belongs”? It does not matter, for here is our mandate as Christians:

The alien who resides with you shall be to you as the citizen among you; you shall love the alien as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt: I am the Lord your God.

Leviticus 19:34

Yours,

Sarah Ngu 吴凯灵

Community Director, Executive Council

PS: A few more resources other than what I linked above…

The Making of Asian America (Erika Lee)

Asian Americans (PBS)

Protect Chinatown (initiative to accompany folks in Chinatown)

The Chinese Must Go (Beth Lew-Williams)

Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans (Ron Takaki)